In the quiet hum of the welding studio, where sparks dance like fireflies and molten metal glows with the warmth of a miniature sun, a profound transformation is taking place. It is here, at the intersection of intense heat and human creativity, that the field of welding metal art transcends its industrial roots to become a medium for breathtaking artistic expression. The recent focus within this community, however, has shifted from the macro to the micro, from the grand sweep of a sculpted curve to the intricate, hidden world of crystal growth within the weld pool. This deep dive into metallurgy is not just for scientists; it is providing artists with an unprecedented lexicon of visual texture and structural integrity, fundamentally changing how they work with metal.

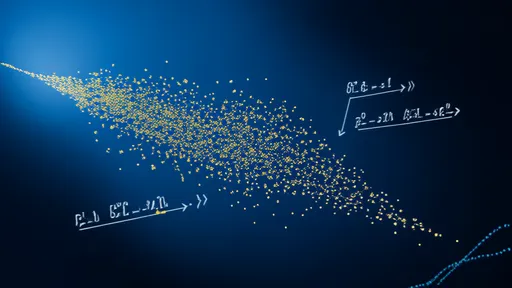

The journey of a weld from liquid to solid is a fleeting, dramatic saga of physics and chemistry. When the welder's arc strikes the base metal, a small reservoir of liquid—the weld pool—is formed. This pool is a superheated crucible, a temporary state of matter where atoms are liberated from their rigid lattice structures and swim in a chaotic, energetic frenzy. The artist’s manipulation of heat input, travel speed, and filler material composition dictates the conditions within this tiny universe. As the heat source moves away, the liquid metal begins its inevitable cool, and in that critical moment of solidification, the future of the weld is written in the language of crystals.

The nucleation of these crystals is the opening act of this microscopic drama. It begins at the edge of the weld pool, where the liquid metal meets the cooler, solid base metal—a region known as the fusion boundary. Here, the temperature gradient is steepest. Atoms, losing their kinetic energy, start to seek stability, latching onto the existing solid crystals of the base metal. This epitaxial growth means the new solid literally grows out from the old, inheriting its crystallographic orientation. The initial formation of these stable nuclei is a delicate process, highly sensitive to impurities, even in minute quantities. Tiny particles of oxides or other compounds can act as heterogeneous nucleation sites, creating new grains with random orientations that disrupt the orderly growth from the fusion line.

Once nucleation occurs, the crystals begin to grow, and their direction is a direct consequence of the artist's technique. The primary direction of growth is opposite to the direction of heat extraction. Since heat is withdrawn through the surrounding solid metal, the crystals stretch inward, toward the center of the weld pool. The shape of the pool itself, controlled by the welder’s travel speed and arc force, dictates the morphology of this growth. A teardrop-shaped pool, resulting from faster travel speeds, encourages crystals to grow competitively from both sides of the pool, meeting in the center to form a distinct line of impurities known as the weld centerline. A more rounded, elliptical pool, achieved with slower speeds or higher heat, allows for crystals to grow in a curved, sweeping pattern from the rear of the pool toward the center, often resulting in a more isotropic and tougher microstructure.

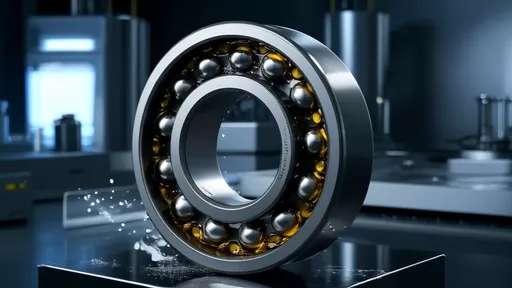

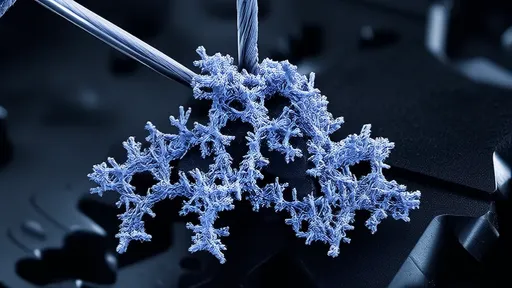

The most common structure observed in welds is the columnar dendritic zone. Here, the crystals grow not as solid blocks, but as intricate, tree-like structures called dendrites. The primary dendrite arm stretches out first, followed by secondary and sometimes tertiary arms branching off perpendicularly. This complex architecture is born from a phenomenon called constitutional supercooling. As the metal solidifies, alloying elements like manganese, silicon, or chromium are rejected from the growing crystal because they don't fit easily into the developing lattice. This enrichment of the liquid ahead of the solidification front lowers its melting point, creating a zone of liquid that is effectively cooler than its actual temperature would normally allow. This unstable condition promotes the rapid, branching growth of dendrites as the system tries to find the most efficient path to solidify. For the artist, this dendritic network is not just structure; it is the source of the subtle, shimmering patterns revealed by etching, a natural fingerprint unique to each weld pass.

Under specific conditions, a different microstructural beast emerges in the very center of the weld: equiaxed grains. Unlike the long, directional columnar grains, these are small, fine crystals with roughly equal dimensions in all directions. They form when the center of the weld pool cools rapidly enough and with sufficient agitation—perhaps from arc oscillations or specific electromagnetic forces—to create a massive amount of nucleation sites throughout the liquid simultaneously. This can be encouraged by the intentional addition of grain refiners, such as titanium or boron, through the filler wire. For the metal artist, achieving an equiaxed zone is often a goal, as this fine-grained structure typically possesses superior mechanical properties, including greater ductility and toughness, which is crucial for large-scale outdoor sculptures facing wind and weather.

This scientific understanding is not confined to textbooks; it is actively being harnessed in studios worldwide. Artists are now orchestrators of crystallization. By carefully selecting their filler alloy—perhaps a stainless steel rich in ferrite-formers for a specific etch response, or a nickel-based alloy for its unique solidification characteristics—they pre-determine the palette of patterns available to them. They manipulate their technique to create specific thermal cycles. A slow, weaving bead with a torch might be used to promote large, sweeping columnar grains for a dramatic wood-grain texture. A rapid, stringer bead with a pulsed arc might be chosen to create a fine, equiaxed structure for a section requiring later cold-forming. The post-weld etching process then becomes a revelatory act, washing away the surface to expose the hidden crystalline artwork beneath, a permanent record of the melt's fleeting moment of creation.

The implications of this knowledge extend far beyond aesthetics. A deep comprehension of solidification cracking, a dreaded defect, allows artists to avoid it. This cracking occurs in the terminal stages of solidification, when a thin film of liquid remains trapped between already-solid dendrites. If the weld is under tension during cooling, this brittle film tears, creating a crack. By understanding that this is most prevalent in wide, concave weld pools with high restraint, an artist can adjust their technique—increasing travel speed, adjusting joint fit-up, or choosing a filler metal with a wider solidification temperature range—to eliminate the problem before it starts. This mastery transforms the artist from a mere craftsperson into a materials scientist, capable of diagnosing and solving structural problems through the fundamental principles of metallurgy.

Looking forward, the fusion of art and science in welded metal is only deepening. Experimental artists are collaborating with metallurgists to explore extreme techniques, such using advanced cooling jets to manipulate temperature gradients in real-time or employing electron beams in vacuum chambers to create utterly unique solidification structures. The weld bead itself is becoming the subject, not just the joining method. In the hands of these modern alchemists, the observation and control of crystal growth within the weld pool has become the ultimate tool, allowing them to freeze a moment of thermodynamic chaos into a permanent, durable, and profoundly beautiful form. The art is no longer just on the metal; it is of the metal, a direct visualization of its most intimate physical journey.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025