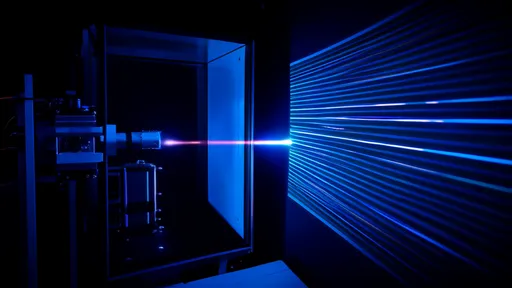

The double-slit experiment stands as one of the most profound and enigmatic demonstrations in the history of physics. Initially conceived by Thomas Young in the early 19th century to demonstrate the wave nature of light, it has evolved, particularly through its quantum mechanical interpretation, into a cornerstone of modern physics that challenges our very understanding of reality. At its heart, the experiment is elegantly simple: a beam of particles, be they photons or electrons, is directed towards a barrier with two narrow, parallel slits. A screen behind this barrier records the pattern of where these particles land.

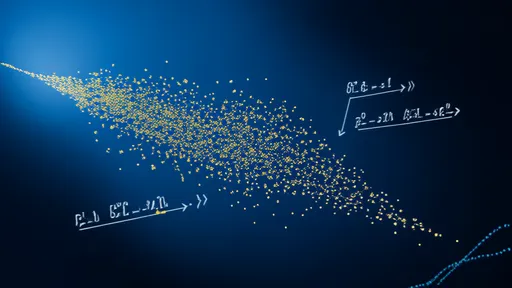

When this experiment is conducted with a continuous stream of particles, one might intuitively expect to see two distinct bands on the detection screen, corresponding to the particles that passed through one slit or the other. However, this is not what occurs. Instead, an interference pattern emerges—a series of light and dark fringes that is the unmistakable signature of wave behavior. The waves emanating from each slit spread out and overlap, constructively interfering where peaks meet peaks (creating bright bands) and destructively interfering where peaks meet troughs (creating dark bands). This result firmly established that light, under these conditions, behaves as a wave.

The plot thickened dramatically when technology advanced to the point where particles could be fired one at a time towards the double slits. The intention was to settle a debate: if particles are sent individually, they cannot possibly interfere with each other, and the wave-like pattern should disappear. The outcome was nothing short of astonishing. Even when particles were emitted singly, with significant intervals between them, the interference pattern gradually built up on the screen over time. Each particle, seemingly acting alone, was still contributing to an overall wave pattern. This suggested a baffling conclusion: each individual particle was effectively passing through both slits simultaneously and interfering with itself. This behavior is a quintessential example of quantum superposition, where a particle exists in multiple states or locations at once until it is observed or measured.

This is where the act of observation introduces a profound paradox. To understand which slit a particle actually goes through, physicists introduced a measuring apparatus to detect the particle's path at the slits. The moment this observation is made—the instant we obtain which-path information—the entire phenomenon changes. The beautiful interference pattern on the screen vanishes. In its place, two simple, stark bands appear, exactly as one would expect from classical particles that have chosen a single, definite path through one slit or the other. The wave-like behavior collapses upon measurement.

The mechanism behind this effect remains one of the deepest puzzles in quantum mechanics. It is not merely a technicality of measurement disturbance; it strikes at the philosophical core of what constitutes reality. The prevailing interpretation, the Copenhagen interpretation pioneered by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, posits that particles do not have definite properties, like a specific position, until they are measured. The act of measurement itself forces the particle's wavefunction—a mathematical description of its quantum state—to collapse from a spread-out probability wave into a single, definite point. The particle is not a localized entity until an observation compels it to be one.

This leads to the unsettling implication that the observer plays an active role in shaping reality. The experiment appears to demonstrate that the mere act of looking, of seeking information, irrevocably alters the outcome of an event. This has spawned countless metaphors and philosophical debates. Does the moon exist when nobody is looking at it? The double-slit experiment suggests that at the quantum level, the answer is not as straightforward as one might think. The universe at its most fundamental level may not be a collection of definite objects but a realm of potentials and probabilities, with observation acting as the catalyst that crystallizes possibility into actuality.

Other interpretations have been proposed to resolve this paradox without granting consciousness or observation such a pivotal role. The de Broglie-Bohm pilot-wave theory, for instance, suggests that particles are indeed point-like and have definite trajectories at all times, but are guided by a hidden "pilot wave" that dictates their motion, creating the illusion of wave-particle duality and explaining the interference pattern. The many-worlds interpretation offers an even more radical solution: every quantum possibility is realized. When a particle reaches the slits, the universe splits into two branches; in one, the particle goes through the left slit, and in another, it goes through the right. The interference pattern is a result of interaction between these parallel universes, and there is no true collapse of the wavefunction.

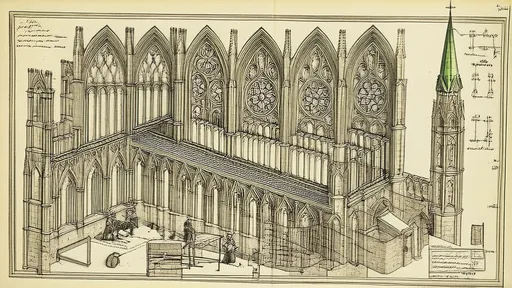

Despite the elegance of these alternative theories, the core mystery of the measurement problem persists. The double-slit experiment has been replicated with increasingly large molecules, pushing the boundaries of where quantum weirdness ends and classical certainty begins. Each successful replication with a more complex system deepens the metaphor: the influence of measurement is a fundamental, not a incidental, feature of our universe.

Beyond the realm of theoretical physics, the implications of this metaphor ripple through other fields. In psychology, it echoes the concept that the act of observing a system, such as a group of people or an individual's behavior, can alter that system's state—a phenomenon known as the Hawthorne effect. In philosophy, it fuels ongoing debates about idealism versus realism, questioning the independence of reality from the mind. It serves as a powerful allegory for how the tools and methods we use to seek knowledge can inevitably shape the answers we receive.

In conclusion, the double-slit interference metaphor transcends its origins in a physics laboratory. It is a enduring testament to the strange and counterintuitive nature of the quantum world, presenting a profound narrative on how interaction and observation are inextricably linked to outcome. It challenges the classical, deterministic view of the universe and suggests that we are not passive witnesses to reality but active participants in its creation. The simple act of looking does not just reveal a pre-existing state; it helps to define what that state is, forever weaving the observer into the fabric of the observed.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025