In the quiet stillness of a forest, the rings of a tree hold more than just the story of its own life. They are, in fact, a meticulously kept archive of the environment, a natural ledger of climate history written in the language of wood. The scientific discipline of dendroclimatology deciphers this language, transforming the seemingly simple growth patterns of trees into a powerful tool for understanding past climates. By studying the width, density, and chemical composition of annual rings, researchers can reconstruct temperature fluctuations, precipitation patterns, and even atmospheric conditions from centuries, and in some cases, millennia ago. This field stands at the fascinating intersection of biology, ecology, and climatology, offering a unique and deeply historical perspective on environmental change that is crucial for contextualizing our current climate crisis.

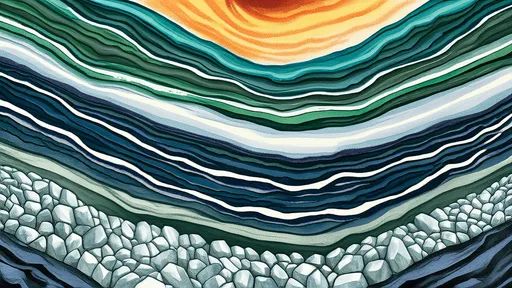

The fundamental principle behind this natural record-keeping is elegantly straightforward. Each year, a tree adds a new layer of wood, known as an annual ring, to its trunk and branches. The character of this ring is profoundly influenced by the environmental conditions the tree experiences during its growing season. In a year with ideal conditions—ample sunlight, sufficient water, and warm temperatures—the tree undergoes vigorous growth, resulting in the formation of a wide, light-colored band of earlywood. Conversely, when conditions are harsh, such as during a drought or an unusually cold summer, growth is stunted, producing a narrow, often denser, band of latewood. The stark contrast between one year’s latewood and the next year’s earlywood creates the visible boundary that defines an annual ring. It is this variation from year to year that forms the basis of the climate record.

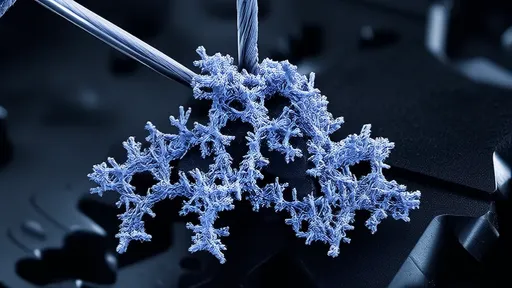

However, the work of a dendroclimatologist is far more complex than simply measuring ring widths. The process begins with the careful selection of trees. Scientists often seek out trees from extreme environments, such as high altitudes or arid sites, where a single factor—like temperature or moisture—is the primary limiting factor for growth. This simplifies the climate signal, making it easier to isolate and interpret. Using specialized hollow borers, researchers extract core samples without harming the living tree. These pencil-thin cores, which contain a complete sequence of rings from bark to pith, are then meticulously prepared, mounted, and sanded to reveal the cellular structure with perfect clarity.

Under the microscope, the story becomes even richer. It is not just the width of the ring that matters, but the anatomy of the cells themselves. In a good year, the xylem cells responsible for transporting water are large and thin-walled. In a stressful year, these cells are smaller, thicker-walled, and more densely packed. Furthermore, advanced techniques like X-ray densitometry allow scientists to measure the wood density within each ring with high precision, a parameter often more sensitive to temperature than ring width alone. The most cutting-edge research even analyzes the stable isotopes of carbon and oxygen trapped within the cellulose of each ring. The ratio of these isotopes can reveal precise details about humidity, rainfall sources, and photosynthetic activity from a specific year in the distant past.

Of course, a single tree’s story could be an anomaly—influenced by a localized event like a rockslide, disease, or animal damage. To build a robust and reliable climate record, scientists must cross-date multiple samples. This involves matching patterns of wide and narrow rings across many trees from the same region, both living and dead. Overlapping the patterns from a living tree with those from a preserved log, and then with an ancient beam from a historical structure, allows researchers to create a continuous chronology that can extend back thousands of years, far beyond the lifespan of any single tree. This master chronology acts as a regional fingerprint of climate, against which individual tree records can be validated.

The insights gained from these woody archives are profound. Dendroclimatological studies have been instrumental in reconstructing past droughts, such as the infamous Medieval Megadroughts in North America, which lasted for decades and likely reshaped ancient Puebloan societies. They have provided evidence of volcanic eruptions, whose ejected particles shield the earth from sunlight, leading to noticeably cooler and narrower rings in the years following the event. These long-term perspectives are invaluable because they reveal the full natural range of climate variability—the droughts, heatwaves, and cold periods that occurred long before human industry began influencing the climate. This establishes the critical baseline needed to distinguish natural cycles from the unprecedented warming trend driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite its power, the method is not without its limitations and challenges. Trees do not respond to climate in a simple, uniform way. Their growth can be a complex response to multiple interacting factors, and this "noise" must be carefully statistically filtered out to isolate the clear climate "signal." Furthermore, the very climate changes scientists are trying to study can themselves affect the tree's response, a problem known as the divergence problem, where tree ring patterns in some cold regions have recently become less correlated with rising temperatures. This underscores the need for continuous refinement of methods and the integration of dendroclimatological data with other climate proxies, like ice cores and sediment layers, to build the most comprehensive picture possible.

In an era of rapid environmental change, the lessons locked in tree rings have never been more relevant. They provide the long-term context that short-term instrumental records cannot, offering a deep-time view of Earth's climate system. By understanding how ecosystems responded to climatic shifts in the past, scientists can better predict how they might respond in the future. The silent, patient growth of trees has given us a unique and powerful archive. As we work to address the challenges of modern climate change, this historical record, written in wood and decoded by science, remains an indispensable guide, reminding us that the environment has always kept a detailed account of its own history.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025