In the intricate world of naval architecture and marine engineering, the study of rudder hydrodynamics stands as a critical pillar for understanding vessel maneuverability. The relationship between the angle of attack of a rudder blade and its steering efficiency is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental principle that dictates the performance, safety, and economic viability of maritime transportation. This deep dive explores the nuanced interplay between these forces, shedding light on the physics that govern a ship's path through water.

The rudder, often described as the ship's steering organ, functions by deflecting water flow. When the helm is turned, the rudder blade pivots, presenting an angle to the oncoming water—this is the angle of attack. It is this angle that generates hydrodynamic lift, a force perpendicular to the direction of flow, which in turn creates a turning moment about the ship's center of gravity. The magnitude of this lift force, and consequently the efficiency of the turn, is profoundly dependent on the angle of attack. At lower angles, the lift increases nearly linearly with the angle. The water flows smoothly over the hydrofoil shape of the rudder, adhering to the surface and creating a pressure difference between the two sides—the fundamental mechanism of lift.

However, this relationship is not infinitely linear. As the angle of attack increases, a fascinating and critical phenomenon occurs: flow separation. Beyond a certain threshold, typically around 15 to 20 degrees for many conventional rudder profiles, the water flow can no longer follow the contour of the rudder blade. It separates from the surface, creating a turbulent wake of eddies and vortices behind the rudder. This separation drastically increases drag—the force opposing the rudder's motion through the water—while the lift force peaks and then begins to decrease. This point is known as the stall angle. A stalled rudder provides significantly diminished turning force and can lead to a loss of effective steering control, a hazardous situation especially in tight maneuvers or adverse weather conditions.

Therefore, maximizing steering efficiency becomes a delicate balancing act. The goal is to operate the rudder at an angle of attack that generates the highest possible lift-to-drag ratio. This optimal angle ensures a powerful turning moment without wasting excessive engine power to overcome drag. Naval architects spend considerable effort designing rudder profiles—from simple flat plates to complex balanced spade rudders and high-lift flap rudders—all with the aim of delaying stall, maximizing lift, and minimizing drag across a range of operational angles. The shape, aspect ratio, and section profile (e.g., NACA airfoil sections) are all meticulously chosen based on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and tank testing to push the performance envelope.

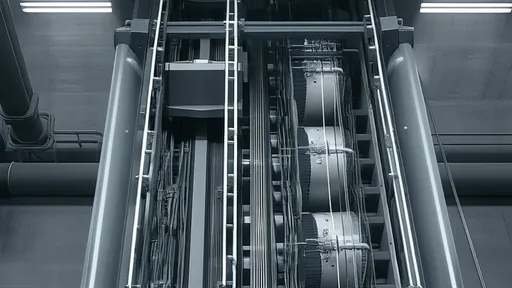

The environment in which a rudder operates further complicates this relationship. The rudder does not work in isolation; it is immersed in the complex wake field of the ship's hull and propeller. The water flowing toward the rudder is already turbulent and unevenly distributed. The propeller's accelerated and rotating discharge current, in particular, dramatically affects the rudder's inflow. This interaction is often leveraged to enhance performance. A rudder placed directly behind a propeller benefits from the higher velocity and better-directed flow, which can delay stall to higher angles of attack and generate greater lift forces for the same rudder angle compared to a rudder operating in open water. This is why the propeller-rudder combination is a quintessential focus of hydrodynamic optimization studies.

Ultimately, understanding the sophisticated dance between the rudder's angle of attack and its steering efficiency is paramount. It informs everything from the initial design of the vessel to the operational procedures followed by the crew on the bridge. Modern systems often include complex control algorithms that manage rudder movement to avoid stall conditions and optimize course-keeping, thereby reducing fuel consumption and improving safety. As maritime industries face increasing pressure to enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impact, the principles of rudder hydrodynamics will continue to steer the course of innovation, ensuring that these ancient yet ever-evolving tools meet the demands of the future.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025