In the heart of industrial operations, where steam powers everything from electricity generation to manufacturing processes, the precise control of steam valves stands as a critical determinant of efficiency and safety. The evolution from manual adjustments to sophisticated automated systems represents not merely a technological shift but a fundamental rethinking of how we manage energy. The automation of steam valve control, particularly for pressure regulation, is governed by a complex interplay of engineering principles, algorithmic precision, and real-time data analytics, forming what can be termed the Automated Equation for Pressure Regulation. This equation is not a single formula but a dynamic framework integrating hardware, software, and control theory to achieve stability in the most demanding environments.

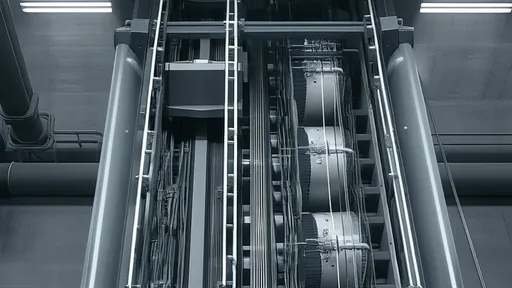

The foundational element of any steam control system is the valve itself—a mechanical device designed to modulate the flow of steam. Traditional valves relied on human operators or basic mechanical regulators, which often led to oscillations in pressure, inefficiencies, and even hazardous conditions under variable load demands. Modern automated valves, however, are equipped with intelligent actuators that respond to electronic signals from a control system. These actuators can be pneumatic, electric, or hydraulic, each selected based on response time, force requirements, and environmental conditions. The valve’s characteristics, such as its flow coefficient and inherent equal percentage or linear flow traits, are baked into the automation logic, ensuring that the mechanical response aligns with theoretical models.

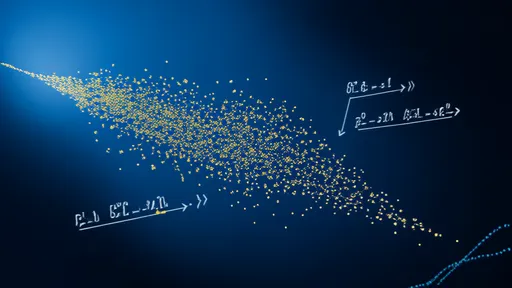

At the core of the automation equation lies the controller, the brain of the operation. Most contemporary systems employ a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller, a versatile algorithm that continuously calculates an error value as the difference between a desired setpoint and a measured process variable—in this case, steam pressure. The proportional term addresses the present error, the integral term accumulates past errors to eliminate residual offset, and the derivative term predicts future errors based on the rate of change. Tuning a PID controller for steam systems is a delicate art; too aggressive, and the system may overshoot or oscillate; too sluggish, and it fails to respond to sudden load changes. Advanced implementations might use fuzzy logic or model predictive control (MPC) for non-linear processes, where the dynamics of steam formation and condensation add layers of complexity.

Feeding the controller is a suite of sensors that provide real-time data on pressure, temperature, and flow rates. High-fidelity pressure transducers and resistance temperature detectors (RTDs) are strategically placed upstream and downstream of the valve to capture the system’s state accurately. The reliability of these sensors is paramount; any drift or failure could lead to catastrophic miscalculations. Thus, automated systems often incorporate redundancy and diagnostic routines to validate sensor integrity. The data from these sensors are filtered and processed to eliminate noise, ensuring that the controller acts on genuine process changes rather than transient artifacts.

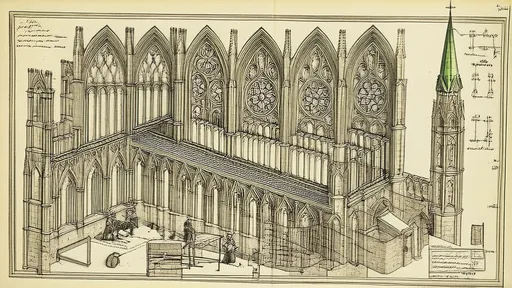

The automation equation extends beyond the PID loop into the realm of system modeling. Engineers develop mathematical models that simulate the thermodynamics and fluid dynamics of the steam system—how pressure waves travel through pipes, how heat loss affects steam quality, and how valve movements impact flow inertia. These models, often derived from first principles or empirical data, allow for predictive adjustments. For instance, if a turbine is about to trip offline, the model can anticipate a pressure surge and preemptively modulate the valve to dampen the effect. This predictive capability transforms the control system from reactive to proactive, minimizing disruptions and enhancing safety.

Integration with broader plant control systems, such as Distributed Control Systems (DCS) or Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA), elevates the automation equation to a system-wide perspective. Here, the steam valve is not an isolated component but a node in a networked ecosystem. It receives setpoints from higher-level optimization algorithms that consider economic dispatch, energy efficiency, and equipment longevity. For example, during low demand periods, the system might reduce pressure setpoints to save energy, while during peaks, it might prioritize stability over efficiency. Communication protocols like Modbus, PROFIBUS, or OPC UA ensure seamless data exchange, while cybersecurity measures protect against unauthorized access that could compromise safety.

Human factors remain integral to the equation. Although automation handles routine regulation, engineers oversee the system, interpreting trends, performing maintenance, and intervening during anomalies. The user interface, whether a graphical mimic diagram on an HMI or a dashboard in a control room, must present information intuitively, highlighting deviations and suggesting actions. Training for operators focuses on understanding the automation’s behavior—knowing when to trust the system and when to override it. This human-machine collaboration is essential for resilience, as no algorithm can account for every unforeseen event.

The benefits of automating steam valve control are profound. Plants achieve tighter pressure control, reducing mechanical stress on pipelines and turbines, which extends asset life and reduces maintenance costs. Energy efficiency improves as steam is generated and utilized at optimal pressures, minimizing waste. Safety is enhanced through rapid response to emergencies, such as pressure excursions that could lead to blowouts. Moreover, the data collected over time provides insights for continuous improvement, identifying patterns that inform better design and operation practices.

Yet, challenges persist. The initial investment in sensors, actuators, and control infrastructure can be significant. Integrating new automation with legacy equipment requires careful planning to avoid compatibility issues. The complexity of tuning and maintaining these systems demands skilled personnel, underscoring the need for ongoing training and support. Additionally, as systems become more connected, they face emerging threats from cyber-attacks, necessitating robust security protocols.

Looking ahead, the automation equation will evolve with advancements in digital twin technology, where a virtual replica of the physical system allows for simulation and testing of control strategies without risk. Artificial intelligence and machine learning could enable self-tuning controllers that adapt to changing conditions autonomously. The integration of IoT devices might lead to even finer granularity in control, with wireless sensors providing data from previously inaccessible points. These innovations promise to make steam valve control more resilient, efficient, and intelligent.

In conclusion, the automation of steam valve control for pressure regulation is a multifaceted equation blending mechanical engineering, control theory, data science, and human expertise. It transforms a fundamental industrial process into a dynamic, optimized, and safe operation. As industries strive for greater sustainability and efficiency, refining this automated equation will remain a priority, driving innovations that resonate across the energy sector and beyond.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025