In the quiet corners of antique shops and family homes, wooden rocking chairs hold more than just sentimental value—they carry within their grains a subtle acoustic record of material aging. Recent interdisciplinary research has revealed that the harmonic vibrations produced by these seemingly simple objects undergo measurable changes as the wood matures and deteriorates, creating what scientists are calling a "sonic fingerprint" of material decay.

The phenomenon centers on how wooden components, particularly those in rocking chairs, respond to rhythmic motion. When a person rocks, the chair's curved runners create a periodic oscillation that generates a complex set of vibrations throughout the structure. These vibrations produce audible and sub-audible frequencies that can be measured using sensitive acoustic equipment. What makes this particularly fascinating is how these harmonic signatures evolve over decades of use and environmental exposure.

Material scientists from the University of Cambridge have been conducting long-term studies on various wooden specimens, including antique rocking chairs dating back to the early 19th century. Their findings demonstrate that as wood ages, its cellular structure undergoes changes that significantly alter its vibrational properties. The gradual loss of moisture content, the breakdown of cellulose fibers, and the development of micro-fissures all contribute to shifting the fundamental frequency and harmonic overtone patterns.

Dr. Eleanor Westwood, lead researcher on the project, explains that "wood behaves like a complex musical instrument that's constantly being retuned by time". Her team's analysis shows that older specimens typically exhibit a lowering of fundamental frequencies by 12-18% compared to newly manufactured replicas made from the same wood species. This frequency drop correlates with the loss of structural stiffness that occurs as lignin deteriorates and cellular walls compress under years of mechanical stress.

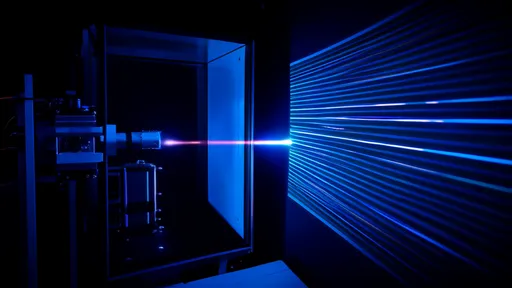

The research methodology involves both laboratory testing and field studies. In controlled environments, researchers subject wood samples to accelerated aging processes while monitoring acoustic changes. Meanwhile, conservationists are documenting vibrations from antique rocking chairs in museum collections and private homes, creating a valuable database of aging signatures across different wood types—from dense oak to more flexible hickory and maple.

What makes this research particularly valuable is its potential application in preservation science. Conservators can now use non-invasive acoustic testing to assess the structural integrity of antique wooden objects without damaging them. By comparing the harmonic profile of a piece against databases of known aging patterns, experts can identify areas of weakness, estimate approximate age, and even detect previous restoration work that might not be visible to the naked eye.

Beyond preservation, these findings are influencing modern furniture design. Engineers are experimenting with treatment processes that stabilize wood's vibrational characteristics, while some manufacturers are developing "aging algorithms" that predict how their products will acoustically mature over time. There's even growing interest in creating digital archives of significant historical pieces—preserving not just their physical form but their unique sonic identities.

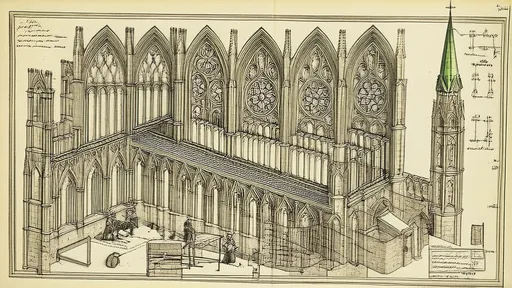

The study of rocking chair harmonics has also revealed surprising consistency in how different wood types age. While initial vibration profiles vary considerably between species, the rate and direction of harmonic shift follow remarkably similar patterns across materials. This suggests underlying universal principles in how cellulose-based materials deteriorate under cyclical stress, principles that may apply to everything from musical instruments to architectural structures.

Perhaps most poetically, this research has given us a new way to listen to history. The gentle creak of a great-grandmother's rocking chair isn't just random noise—it's the voice of the wood itself, telling the story of countless hours of use, seasonal changes in humidity, and the slow, inevitable transformation that comes with time. As recording technology improves, researchers hope to create increasingly detailed acoustic maps of material aging, potentially preserving these sonic histories even after the physical objects are gone.

Future research directions include expanding the study to other wooden objects subjected to rhythmic stress—porch swings, wooden bridges, even dance floors. There's also work being done to correlate specific environmental conditions (coastal humidity versus arid desert climates) with distinctive aging patterns in the harmonic profiles. This could eventually allow historians to determine not just how old an object is, but where it has spent its life.

The humble rocking chair, often seen as a simple relic of quieter times, has emerged as an unexpected scientific instrument—one that measures the passage of years not in ticks of a clock, but in shifts of frequency and changes in tone. Its gentle rock continues to soothe children to sleep, but now we understand that with each forward and backward motion, it's also recording the subtle music of material transformation, creating a harmonic diary written in vibration rather than ink.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025