In the intricate world of mechanical engineering, few topics capture the elegance of precision like the meshing of gears, particularly those designed with involute tooth profiles. This mathematical marvel, often overshadowed by more flashy technological advancements, remains a cornerstone of modern machinery, from humble wristwatches to colossal industrial equipment. The story of involute gearing is not merely one of mechanical function but a testament to how mathematical principles can be harnessed to create harmony in motion.

The fundamental concept behind the involute tooth shape lies in its generation from a base circle. Imagine unwinding a taut string from a cylinder; the path traced by the end of that string forms an involute curve. When applied to gear teeth, this geometry ensures that the point of contact between two meshing gears always occurs along a straight line—known as the line of action—passing through the pitch point. This constant direction of force transmission is pivotal. It eliminates sliding friction at the pitch point, where pure rolling contact takes place, thereby reducing wear, minimizing energy loss, and enabling smoother, quieter operation even under substantial loads. Unlike cycloidal teeth, which were historically used but are sensitive to center distance variations, involute gears maintain correct angular velocity ratios even when the actual center distance between gears deviates slightly from the theoretical value. This inherent forgiveness, a gift of their mathematical origin, makes them exceptionally practical for real-world applications where perfect alignment is often an ideal rather than a reality.

Delving deeper, the beauty of the involute profile is rooted in its self-similarity and conjugate action. As two involute gears rotate, the teeth engage and disengage along the flanks of these meticulously calculated curves. The contact begins near the root of the driving gear tooth and the tip of the driven gear tooth, then progresses smoothly across the active profile. Throughout this motion, the common normal at the point of contact always tangents the base circles of both gears and intersects the line of centers at a fixed point—the pitch point. This kinematic behavior guarantees a constant velocity ratio, meaning the driven gear rotates at a perfectly uniform speed relative to the driver, a non-negotiable requirement for precision machinery like automotive transmissions or robotic actuators. Any deviation from this constancy would introduce vibrations, noise, and ultimately, failure.

The mathematics governing this perfection is both elegant and complex. The involute function itself, often denoted as inv(α) = tan(α) - α (where α is the pressure angle), is a transcendental equation that defines the curve's unique properties. Pressure angle, a critical design parameter typically set at 20° or 14.5° for standard gears, influences the gear's strength, noise level, and tendency to undercut. A larger pressure angle yields stronger teeth with a broader base but higher bearing loads and increased noise. The precise calculation of tooth thickness, base pitch, and contact ratio all stem from this underlying mathematics. The contact ratio, must be greater than one to ensure at least one pair of teeth is always in contact, guaranteeing continuous, uninterrupted power flow. This seamless transfer of force is what makes involute gearing so exceptionally reliable.

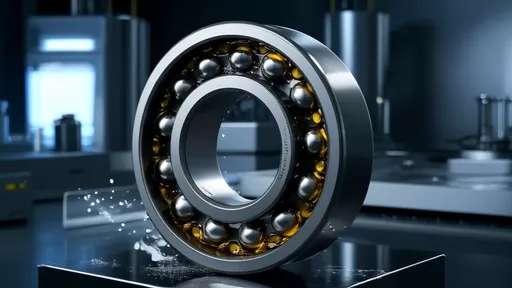

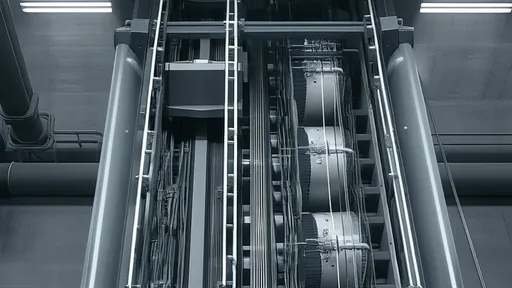

Manufacturing these perfect forms is a feat of technological prowess. Modern processes like hobbing, shaping, and grinding have evolved to create involute teeth with micron-level accuracy. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines, guided by sophisticated software, translate the mathematical ideal into physical reality. The quality of a gear is often judged by its deviation from the perfect involute profile, measured using specialized gear metrology equipment like coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) or gear analyzers. This relentless pursuit of perfection in manufacturing underscores the critical importance of the mathematical design; even the slightest imperfection can lead to premature wear, increased noise, and catastrophic failure in high-performance applications like aerospace or wind turbines.

Beyond its mechanical superiority, the involute profile's legacy is its democratization of precision. The standardization of gear systems around the involute principle, championed by engineers and organizations like the American Gear Manufacturers Association (AGMA) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), has created a universal language for gear design. This allows gears manufactured by different companies, in different countries, to mesh together flawlessly. It is this interoperability, born from a shared commitment to a mathematical truth, that has powered global industrialization and innovation.

In conclusion, the meshing of involute gears is far more than a mere mechanical interaction; it is a dance dictated by the unwavering rules of geometry and calculus. It is a brilliant application of abstract mathematics solving a fundamental engineering challenge: the efficient, smooth, and reliable transmission of power. In an age of digital marvels, the silent, steadfast rotation of involute gears remains a powerful reminder of the profound beauty that can be found in precision engineering, a beauty that is, at its heart, profoundly and beautifully mathematical.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025