In the quiet corners of theoretical physics and the bustling laboratories of psychological research, an unusual dialogue is emerging—one that bridges the abstract mathematics of quantum mechanics with the intimate complexities of human emotion. The catalyst for this interdisciplinary exploration is none other than one of science’s most famous thought experiments: Schrödinger’s Cat. Traditionally a parable about quantum superposition and observer effect, the paradox of the cat both dead and alive in a sealed box has begun to resonate in an unexpected domain—the study of the human psyche. Researchers are now probing whether the principles underlying this quantum conundrum might offer a metaphorical, or perhaps even mechanistic, framework for understanding emotional ambiguity, unresolved feelings, and the dualities that define so much of our inner lives.

The original Schrödinger’s Cat scenario, devised by physicist Erwin Schrödinger in 1935, was intended as a critique of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. In this setup, a cat is placed in a sealed box with a radioactive atom, a Geiger counter, a hammer, and a vial of poison. If the atom decays, it triggers the Geiger counter, which releases the hammer to break the vial, killing the cat. According to quantum theory, until the box is opened and observed, the atom exists in a superposition of decayed and not decayed states. Consequently, the cat is theoretically both alive and dead simultaneously—a state that collapses into one reality only upon measurement. While physicists continue to debate the interpretations and implications of this paradox, its symbolic power has escaped the confines of physics, capturing the imagination of psychologists and philosophers alike.

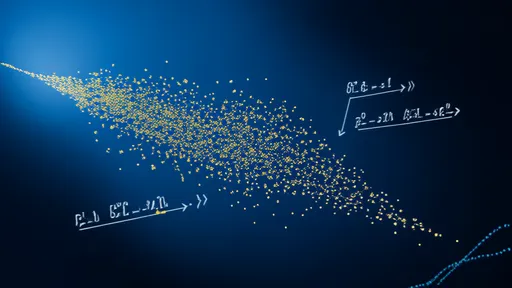

This migration of ideas from quantum theory to psychology isn't entirely unprecedented. The field of quantum cognition, for instance, has already applied quantum mathematical models to explain certain cognitive phenomena that classical probability theory struggles with, such as order effects in decision-making or the violation of the sure thing principle. However, the application to emotion is a more recent and speculative venture. It asks a provocative question: could human emotions exist in a state of superposition analogous to quantum particles? Can a person simultaneously hold two contradictory emotional states—joy and sorrow, love and hate, hope and despair—without resolving into a single, definitive feeling until some form of internal or external "observation" occurs?

Consider the common experience of ambivalence. In relationships, individuals often report feeling both deep affection and intense frustration toward a partner, especially during conflicts or periods of uncertainty. Classically, one might describe this as mixed feelings or emotional conflict. But through the quantum lens, this might be framed as an emotional superposition—a genuine coexistence of opposing states that do not simply cancel each other out but remain simultaneously present and potent. The act of "opening the box," in this context, could be a decisive conversation, a moment of clarity, or an external event that forces a collapse into a more defined emotional reality, such as reconciliation or breakup.

This metaphorical mapping extends beyond interpersonal dynamics to intrapsychic experiences. Trauma survivors, for example, might grapple with simultaneous feelings of strength and vulnerability, safety and threat, even years after the traumatic event. The psychological state doesn't always neatly settle; it may hover in a liminal space where contradictory emotions are both true. Therapeutic interventions, then, could be seen as observational acts that help collapse these superpositions into more integrated, manageable states. The therapist’s office becomes the laboratory where observation facilitates resolution.

But the analogy is not merely poetic; some researchers are exploring formal models. Drawing on the mathematical formalism of quantum theory—state vectors in Hilbert space, probability amplitudes, and projection operators—they are constructing frameworks to represent cognitive and emotional states. In such models, an emotion isn't a fixed point but a vector that can be in a superposition of basis states (e.g., happy and sad). The process of decision-making or emotional resolution involves a measurement-like operation that projects this superposition onto a particular outcome. This approach can quantitative capture the interference effects observed in human emotions, where the presence of one feeling influences the intensity or probability of another in ways that classical models cannot easily explain.

Critics, however, urge caution. They argue that while the quantum metaphor is intellectually stimulating, it risks being just that—a metaphor. Human emotions are biological, neurological, and phenomenological phenomena, not quantum systems. The brain may not operate at a quantum level in its cognitive processes; indeed, most neuroscientists believe that classical physics suffices to explain neural activity. Applying quantum concepts to psychology could therefore be seen as reductive or misleading, importing exotic physics where simpler psychological theories would suffice. Moreover, the mystery of quantum measurement itself—what exactly constitutes an observation and causes collapse—remains unsolved in physics, so transplanting this problem into psychology might compound rather than clarify the complexities.

Despite these criticisms, the psychological mapping of Schrödinger’s cat paradox opens fertile ground for interdisciplinary dialogue. It encourages a fresh perspective on the nature of emotional reality, one that embraces uncertainty, duality, and the power of perspective. In a world where human experiences are increasingly recognized as non-binary and multifaceted, this quantum-inspired view offers a language to describe the gray areas—the emotional superpositions that define so much of our existence. It reminds us that, like the cat in the box, our feelings can be both real and unresolved until the moment we look within.

As research progresses, the challenge will be to move beyond metaphor and explore whether quantum mathematical tools genuinely offer predictive power and deeper insight into emotional processes. Whether literally or figuratively, the entanglement of quantum physics and psychology underscores a broader truth: that the quest to understand the universe and the quest to understand the human heart are, in their own ways, profoundly connected. In the superposition of emotions, we may find not only a reflection of quantum weirdness but also a new appreciation for the complexities that make us human.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025