In the intricate dance of mechanical systems, few principles are as fundamental and pervasive as the conservation of energy. This immutable law, which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed but only transformed or transferred, finds a particularly elegant and practical manifestation in the operation of modern elevators. The seemingly simple act of an elevator car ascending and descending is, in fact, a masterclass in applied physics, with the counterweight system serving as its star pupil. This sophisticated balancing act is not merely a matter of convenience; it is a critical engineering solution that directly dictates the system's efficiency, safety, and operational cost.

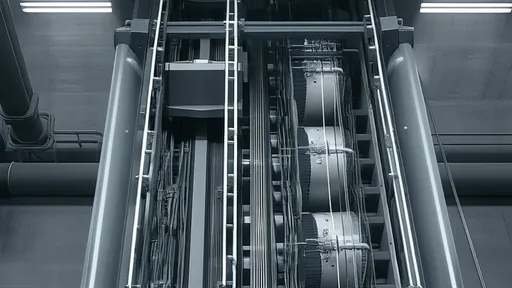

The core challenge in vertical transportation is the immense amount of energy required to lift a heavy cab, along with its human cargo, against the unyielding force of gravity. Without a countermeasure, the electric motor would need to be enormously powerful to provide the necessary torque for ascent, and the braking system would be under tremendous strain to control the potential energy gained during the descent. This is where the principle of energy conservation is ingeniously leveraged. By introducing a counterweight on the opposite side of the sheave (the pulley wheel), engineers create a system that is perpetually seeking equilibrium.

The mass of the counterweight is meticulously calculated. It is typically set to be equal to the weight of the elevator car itself plus approximately 40 to 50 percent of its maximum rated load. This specific ratio is the key to the system's brilliance. When the elevator is half full, the system is nearly perfectly balanced. The gravitational potential energy of the counterweight almost perfectly offsets that of the car. In this state, the motor requires a minimal input of electrical energy to initiate movement and overcome friction; its primary role is to nudge the system out of balance and control its motion, rather than to perform the Herculean task of lifting the entire mass.

Consider the energy transformations during a typical journey. As a loaded car begins its ascent, it gains gravitational potential energy. Simultaneously, the counterweight, which is descending, loses an almost equivalent amount of potential energy. The energy lost by the counterweight is effectively transferred to help lift the car. The motor merely supplements this energy transfer, compensating for inefficiencies and providing acceleration. Conversely, during a descent, the situation is reversed. The now heavier car possesses significant potential energy, which, as it falls, is converted into kinetic energy. Instead of allowing this energy to be dissipated wastefully as heat in the brakes, the system uses it to help lift the counterweight. The motor acts as a generator, converting this excess kinetic energy back into electrical energy through regenerative braking, which can often be fed back into the building's power grid.

This regenerative process is a direct and powerful illustration of energy conservation in action. The electrical energy supplied to the motor is not solely used to create movement; a substantial portion of it is recovered and reused. This dramatically reduces the net energy consumption of the elevator, making modern high-rise buildings significantly more sustainable. The counterweight system transforms the elevator from a mere energy consumer into a partial energy-recycling device.

Beyond energy efficiency, the counterweight is paramount for safety and control. A balanced system places far less stress on the motor, cables, and brakes, leading to reduced wear and tear and longer component lifespans. It ensures that the traction between the steel ropes and the sheave is maintained, which is the fundamental principle behind the elevator's grip and prevents the dreaded scenario of the car free-falling. In the event of a power failure, a well-balanced system behaves predictably, allowing safety brakes to engage more effectively. The counterweight also minimizes the load on the building's structure itself, as the forces are largely contained within the balanced loop of the car and the weight, rather than being transferred downward.

The design and implementation of these systems are a testament to precision engineering. Every variable, from the weight of the guide rails and cables themselves to the expected passenger load patterns, is factored into the complex calculations. Modern "weightless" systems, such as machine-room-less (MRL) elevators, have pushed this innovation further by using permanent magnet motors and advanced variable-frequency drives that optimize energy use with even greater precision, all while still relying on the timeless counterweight principle.

In conclusion, the humble counterweight in an elevator is far more than a block of metal at the end of a rope. It is the physical embodiment of the law of conservation of energy, a silent partner that enables the smooth, efficient, and safe vertical transit we take for granted. It demonstrates how a profound understanding of fundamental physics allows engineers to create systems that work in harmony with natural laws, turning potential energy from a liability into an asset. This elegant solution stands as a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most advanced technological marvels are those that cleverly manipulate the basic principles of our universe.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025