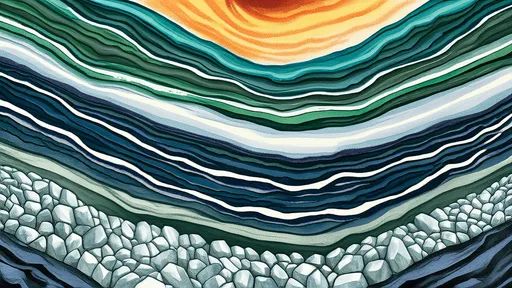

The Earth's crust is a dynamic archive, its rocky layers holding secrets of planetary transformation written in mineralogical code. Few processes capture this geological drama as profoundly as metamorphism—the profound alteration of rocks under the immense pressures and searing temperatures generated by the relentless dance of tectonic plates. It is a story not of melting, but of solid-state rebirth, where existing minerals become unstable and recrystallize into new, denser assemblages, creating a permanent record of the titanic forces that shaped them.

At the heart of understanding any rock's metamorphic history is the concept of metamorphic facies. These are not specific rock types, but groups of mineral assemblages that indicate a specific range of pressure and temperature conditions. A geologist examining a slab of metamorphic rock is essentially a detective reading a pressure-temperature diary. The presence of minerals like glaucophane and lawsonite points directly to the high-pressure, low-temperature conditions of a blueschist facies rock, a telltale sign of its origin in a subduction zone where oceanic crust is forced rapidly down into the mantle. Conversely, the mineral sillimanite speaks of the intense heat and moderate pressure found in the deeper parts of continental collision zones, characteristic of the amphibolite or granulite facies. By meticulously mapping the distribution of these facies, we can reconstruct the ancient geothermal gradient—the rate at which temperature increased with depth—in that specific tectonic environment, painting a vivid picture of the crust's thermal structure millions of years ago.

The most direct tectonic driver of metamorphism is the colossal convergence of continental plates. When continents collide, they crumple and thicken the crust, stacking rock upon rock in massive thrust sheets. This crustal thickening creates the dual engine of metamorphism: the immense lithostatic pressure from the weight of overlying rock and the increasing geothermal heat with depth. This combination typically produces Barrovian-type metamorphism, named after the Scottish Highlands where it was first studied. Here, we see a classic sequence of mineral zones, from chlorite and biotite at lower grades to garnet, staurolite, kyanite, and finally sillimanite at the highest grades, forming a predictable pattern that mirrors the increasing intensity of deformation and burial. The resulting rocks, such as schists and gneisses, form the core of the world's great mountain ranges, from the Himalayas to the Alps, their foliated textures a frozen snapshot of the directed pressures they endured.

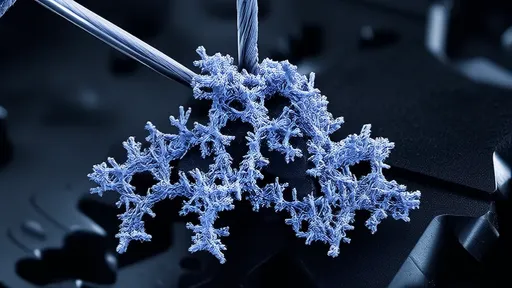

In stark contrast to the continental collisions, the subduction zone presents a unique and geologically fascinating metamorphic environment. Here, cold, water-saturated oceanic crust is pulled downward into the mantle at a rate that often exceeds the conductive heating time. This creates an unusual low-thermal-gradient regime: pressure increases dramatically due to the rapid descent, but temperature rises relatively slowly. This paradox generates the high-pressure, low-temperature (HP-LT) conditions that are the hallmark of blueschist and eclogite facies metamorphism. The formation of minerals like glaucophane (which gives blueschist its name) and the dazzling red pyrope garnet combined with omphacite in eclogite requires these specific, counterintuitive conditions. Eclogite, in particular, is incredibly dense, and its formation is a crucial driver of the negative buoyancy that pulls oceanic plates into the mantle, essentially acting as a gravitational engine for plate tectonics itself. The preservation of these rocks, which are unstable at the surface, requires their relatively rapid exhumation back to the crust, often through complex mechanical processes within the subduction channel.

While convergent boundaries dominate the high-stakes world of regional metamorphism, the slow, steady divergence of plates at mid-ocean ridges creates its own distinct metamorphic signature. Here, the pervasive circulation of seawater through the fractured, hot oceanic crust drives hydrothermal metamorphism. This is not a story of great pressure, but of intense chemical exchange between hot rock and mineral-rich fluids. The primary mineralogy of the basaltic crust—rich in olivine and pyroxene—is altered to a stable secondary assemblage including chlorite, epidote, and serpentine. This process, known as seafloor alteration, is fundamental: it hydrates the oceanic crust, removes certain elements from the ocean, and adds others, profoundly influencing ocean chemistry. More importantly, this hydrated crust is what later enters the subduction zone, its water content playing a critical role in promoting melting in the overlying mantle wedge and thus fueling the volcanic arcs that line our continents.

Deciphering a rock's P-T-t path (Pressure-Temperature-time path) is the ultimate goal in unraveling its metamorphic history. This is not a single point but a trajectory—a loop or a curve on a pressure-temperature diagram that traces the rock's journey as it was buried, heated, possibly compressed, and finally exhumed back towards the surface. We can reconstruct these paths using geothermobarometry, which involves analyzing the composition of certain minerals that act as natural thermometers and barometers. For example, the ratio of magnesium to iron in garnet crystals coexisting with other minerals like biotite or pyroxene can be used to calculate the temperature of formation. Similarly, the content of jadeite in clinopyroxene or of calcium in garnet can be a sensitive indicator of pressure. By analyzing different zones within a single crystal that grew over time, we can sometimes piece together a detailed segment of the rock's entire voyage through the crust.

The implications of understanding metamorphic history extend far beyond academic curiosity. Metamorphic rocks are intimately linked to the formation of major economic mineral deposits. The fluids liberated during devolatilization reactions—as minerals like chlorite or serpentine break down under heat—are hot, acidic, and laden with dissolved metals. As these fluids migrate through fractures and into cooler surrounding rock, they precipitate their metallic cargo, forming valuable ore deposits of gold, copper, zinc, and tungsten. Furthermore, the processes of metamorphism play a critical role in the deep carbon cycle. Carbonate rocks subducted into the mantle can release their carbon through metamorphic reactions, which may then be returned to the atmosphere via volcanism, or alternatively, be stored deep within the Earth for millennia. Understanding the stability of these carbonate minerals under extreme conditions is thus vital for modeling the long-term evolution of Earth's climate.

In conclusion, the metamorphic history locked within recrystallized rock is a profound narrative of planetary dynamics. It is a direct consequence of and a key witness to the powerful forces of plate tectonics. From the crushing depths of subduction zones where eclogites form to the heated cores of mountain belts where gneisses are born, each metamorphic rock is a page in Earth's autobiography. By learning to read the mineralogical text, we do more than just understand the past; we gain critical insights into the mechanisms that shape our world's topography, drive its geochemical cycles, and concentrate the resources upon which modern society depends. The study of metamorphism remains a primary tool for unlocking the secrets of our planet's continuous and dynamic transformation.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025