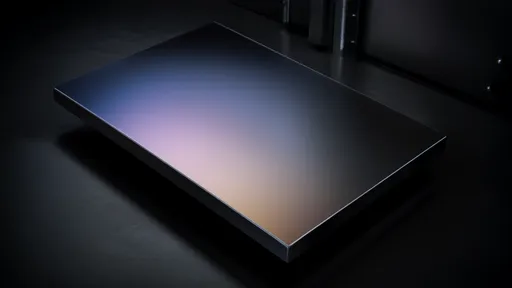

In the rarefied world of fine art and horology, few techniques command as much respect and mystique as Grand Feu enameling. This ancient art, whose name translates to "Great Fire" from French, represents the pinnacle of enamel work, distinguished by its extraordinary durability and sublime beauty. The process involves fusing powdered glass to metal through successive firings in a kiln at temperatures exceeding 800 degrees Celsius. The resulting surface is not merely a layer of color but a metamorphosed, glass-like finish that is virtually impervious to fading, scratching, and the ravages of time. It is a testament to human ingenuity and patience, a dance with elemental forces that few artisans dare to master.

The core of the Grand Feu challenge lies in its unforgiving nature. Unlike modern painting or printing techniques, there is no margin for error, no command-Z to undo a mistake. Each layer of enamel, meticulously applied by hand, must be fired separately. The artist must possess an almost supernatural intuition for how the minerals and oxides in the enamel will react to extreme heat. A misjudgment of a few degrees in temperature or seconds in timing can result in a cracked surface, a clouded opacity, or a color that is catastrophically off-target. The entire piece, often representing dozens of hours of labor, can be ruined in an instant. This high-stakes process is what separates true Grand Feu from other enameling techniques and why it remains the gold standard.

Perhaps the most profound frontier in this art form is the pursuit of color stability under such extreme conditions. The palette available to the Grand Feu enameler is not infinite; it is dictated by chemistry and physics. Certain pigments, vibrant at room temperature, simply cannot survive the inferno of the kiln. Cobalt oxide yields a magnificent, stable blue. Iron oxides can produce a range of reds, browns, and blacks. Copper compounds can create greens and turquoises. But the quest for a perfect, consistent, and stable pure white, a brilliant scarlet, or a specific shade of violet can become an artist's lifelong obsession. These colors represent the absolute limits of the technique, the point where art pushes against the immutable laws of science.

The journey of a Grand Feu piece begins long before it sees the inside of a kiln. It starts with the creation of the base, typically gold, silver, or copper, which is painstakingly prepared and often engraved or guillochéd with intricate patterns that will play with light beneath the translucent enamel. The enameler then grinds the glass powder into a fine paste with water or oil. Applying this paste is an exercise in supreme control; the thickness must be perfectly even to ensure consistent color and avoid bubbling or cracking during firing. The piece is then left to dry completely before its first encounter with the fire, a moment always fraught with anticipation and anxiety.

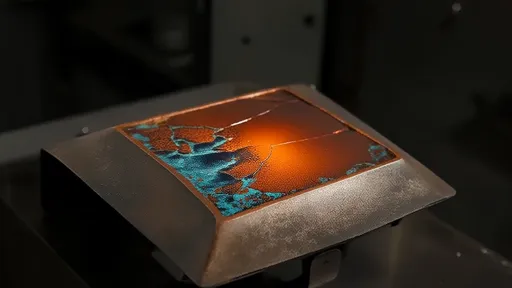

The kiln itself is a crucible of transformation. As the temperature soars, the powdered glass melts, flows, and vitrifies, bonding permanently with the metal substrate. The artist must monitor the process closely, watching for the specific moment when the enamel takes on a characteristic glow or "wet" look, signaling that it has fully matured. Removing it too early leaves a grainy, unfinished surface. Leaving it a moment too long can cause colors to burn, darken, or become muddy. For pieces requiring multiple colors, this entire cycle is repeated for each hue, with masks made of fine gold or platinum foil—known as cloisonné—or reserved areas of metal—champlevé—preventing the colors from bleeding into one another. Each firing is a gamble, increasing the statistical probability of failure.

Master enameler Isabelle Beaumont once described opening the kiln door after a firing as "theater." "There is the smell of hot metal and the intense heat washing over you," she says. "But there is silence. You peer in, holding your breath, looking for that perfect, glossy surface. Sometimes you exhale in triumph. Other times, your heart simply breaks. You learn to mourn quickly and begin again. The fire is a brutal but honest critic." This emotional rollercoaster is an intrinsic part of the craft, a price paid for working at the very edge of what is possible.

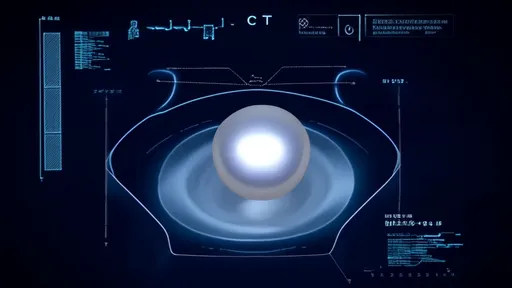

In contemporary applications, particularly in high-end watchmaking, the limits of Grand Feu are being tested like never before. Watch dials are minuscule canvases, often requiring microscopic details and text to be rendered in enamel. The demand for new, vibrant colors to satisfy modern aesthetics pushes chemists and artisans to collaborate on developing new stable compounds. Some manufactures have achieved remarkable feats, creating dials with gradients of color or incorporating minute enameled sculptures. Yet, for every success, there are countless failures that are never seen by the public, shattered or discarded pieces that represent the steep cost of innovation at the thermal frontier.

The future of Grand Feu enameling is a fascinating paradox. It is an art form steeped in centuries of tradition, yet it is not stagnant. Modern technology, such as digitally controlled kilns that offer unparalleled precision in temperature ramping and holding, provides new tools for the artist. However, the fundamental challenge remains human. It requires the steady hand, the keen eye, and the intuitive understanding of materials that can only be developed through decades of practice. The ultimate limit of Grand Feu is not found in the kiln or the chemical composition of the enamel, but in the artist's ability to harmonize with these elements, to achieve a state of grace under fire. It is this human element, this relentless pursuit of beauty against impossible odds, that ensures Grand Feu will continue to captivate and challenge artisans for centuries to come.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025