In the hushed halls of art conservation studios and the vibrant workshops of contemporary artisans, a quiet revolution is taking place. The ancient and extraordinarily painstaking art of micro-mosaic, a technique once thought to be nearly extinct, is experiencing a profound and beautiful renaissance. This is not merely a revival of old methods; it is a reclamation of a heritage, a fusion of historical reverence with modern innovation, allowing artists to recreate iconic masterpieces with tens of thousands of slivers of colored glass, each piece a testament to human patience and vision.

The story of micro-mosaic begins in the grand workshops of 18th-century Rome. Evolving from the larger, more traditional Roman mosaics that adorned floors and walls of villas and basilicas, micro-mosaics (micromosaici) were conceived as portable artworks. Artisans, seeking to capture the exquisite detail and color of paintings for the Grand Tour market, developed a method using incredibly tiny, specially cut pieces of glass, known as tesserae. These tesserae, some no larger than a pinhead, were made from enamel-like glass rods called smalti filati, which could be pulled into delicate threads while molten, allowing for an unprecedented palette of colors and gradients. The most celebrated early examples depicted pastoral scenes, famous ruins, and beloved artworks, set into everything from large tabletop pictures to miniature jewelry and snuffboxes, captivating aristocrats and collectors across Europe.

For nearly two centuries, the secrets of the craft were guarded within a few Italian families and workshops. The industrial revolution and shifting artistic tastes, however, saw a steep decline in its practice. The immense time, skill, and cost required made it economically unviable, and by the mid-20th century, only a handful of elderly masters kept the knowledge alive, their craft on the precipice of being lost forever. The tools—specialized tweezers, micromanipulators, and the proprietary formulas for the colored glass—were gathering dust. It seemed micro-mosaic was destined to become a footnote in art history, a beautiful but obsolete technology.

The tide began to turn as a new generation of artists and art historians, armed with a growing appreciation for artisanal craftsmanship and 'slow art', went in search of these last masters. They were not content to simply document a dying art; they sought to learn it, to breathe new life into its core principles. This modern revival is characterized by a dual mission: the meticulous restoration of priceless historical micro-mosaics and the creation of ambitious new works that push the boundaries of the medium. Studios now employ high-resolution digital imaging to analyze old masters' techniques, reverse-engineering the placement and color choices of thousands of individual tesserae in works displayed in the Vatican Museums or the Hermitage.

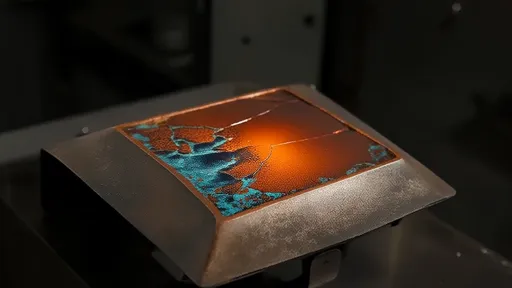

The process of creating a new micro-mosaic, especially one aiming to replicate a famous painting, is an endeavor that borders on the monastic. It begins not with glass, but with a deep study of the source material. The artist must deconstruct the painting—a Caravaggio, a Van Gogh, a Waterhouse—not into brushstrokes, but into an intricate map of pure color and light. A custom palette of several thousand shades of glass must be prepared or sourced, each rod meticulously cataloged. The base, often a stable copper or slate panel treated with a mastic adhesive, becomes the canvas.

Then, the true test of patience begins. Using tweezers under powerful magnification, the artist selects each minute piece of glass, often shaping it further with a fine blade to achieve the exact form needed to follow the contour of a lip or the fold of a robe. The pieces are set not in straight lines, but in flowing, organic patterns that mimic the direction of the original brushwork, a technique known as andamento. A single square inch of the mosaic can contain hundreds of individually placed tesserae. A portrait might require over 10,000 pieces; a larger, complex figurative scene can easily demand 30,000 to 50,000. The work is punishing on the eyes and the spirit, often progressing at a rate of mere square centimeters per day. It is a meditative practice, a dialogue between the artist, the material, and the ghost of the original painter.

The final transformative step is grouting and polishing. A specialized compound is worked into the infinitesimal gaps between the glass pieces, unifying the surface. Once set, the entire piece is polished to a gentle sheen. This is when the magic happens: the light catches the myriad glass facets, and the mosaic ceases to be a collection of disjointed parts. It coalesces into a luminous, vibrant whole, possessing a depth and radiance that is unique to the medium. It does not merely copy the painting; it translates it into a new language—one of light, texture, and incredible durability, destined to last for millennia.

The implications of this revival extend far beyond the creation of beautiful objects. In the world of art conservation, these new masters are invaluable. Their deep, practical understanding of materials and techniques allows them to undertake the restoration of historic micro-mosaics with a peerless authority. They can replicate lost tesserae with chemically identical glass, stabilize weakened structures, and clean centuries of grime without damaging the delicate surface, ensuring these treasures survive for future generations. Furthermore, contemporary artists are using the medium for original works, moving beyond reproduction to explore abstract concepts, portraiture, and modern narratives, proving that micro-mosaic is a living, evolving art form.

The revival of micro-mosaic is a powerful counter-narrative in our age of mass production and digital ephemerality. It is a defiant celebration of the human hand, of time invested rather than saved, and of the tangible beauty that results. Each completed piece, composed of thousands of glimmering fragments, stands as a monumental achievement. It is a bridge across centuries, connecting the skilled hands of an 18th-century Roman artisan with those of a 21st-century artist, both united in their pursuit of capturing light, color, and soul in the most demanding of mediums. This is more than a craft revival; it is the rediscovery of a language for making the sublime tangible, one tiny piece of glass at a time.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025